Design Engineering seems to be having a moment.

There have been recent posts like Vercel's that talk about their design engineering practice, the post by David Hoang speaking to what the role is and why it will be critical in the coming decade, and countless Twitter posts expanding on all of these ideas.1

Truthfully, design engineering has existed in many forms over many years — creative technologists, Flash developers, design technologists, UX engineers: the list goes on ad infinitum.2 Each has come with variations on the tools, on the broad scope, and on the specifics of what this role entails given the needs and context of the industry at the time. But with every iteration, some of the core aspects of what make these people different from pure software designers or engineers have remained the same — and the reason why I want to focus on these attributes in this post. I hope that focus makes the definition of a design engineer for you more clear, especially as it continues to evolve in the future.

As someone who built a career in software as both a design engineer as well as a leader building organizations centered around that work, I have a unique perspective on the role. So, I'm going to share a more personal, raw take that I've developed over the last decade, particularly from my experience as a practitioner earlier in my tenure — and why it's becoming increasingly critical to the way we build software in this moment.

This is the first in a series of posts I'm writing on this topic.3

#What Makes a Design Engineer?

For many people, design engineering can be narrowed in by the tools that they use — are they a designer who knows how to sling some React? Or are they an engineer that has an eye for design and is comfortable in Figma? But after being in this role for the last decade, the best way I would define this practice is to focus on the high-level attributes and outcomes of what being a design engineer entails when building software:

Design engineering is living at the intersection of those practices, and using a broad understanding of both sides to build with significant autonomy, practice and teach great software craft, and elevate the final fidelity of what's made from start to end.

With these attributes for a design engineer, the practice can manifest in different ways and types of roles within an organization that builds software — be it roles focused on design systems/infrastructure, ones focused on prototyping new ideas, or ones focused on building and shipping products/experiences with craft at its core. I've been lucky to experience all of these variations in a design engineering role in my career. I'll write more about these sub-roles and distinctions in detail with another post in the near future.4

So, what follows is how I've seen those 3 fundamental attributes of design engineering applied to my work and the work of others over the last decade, and why these attributes are core to how I define design engineering.

#Build With Significant Autonomy

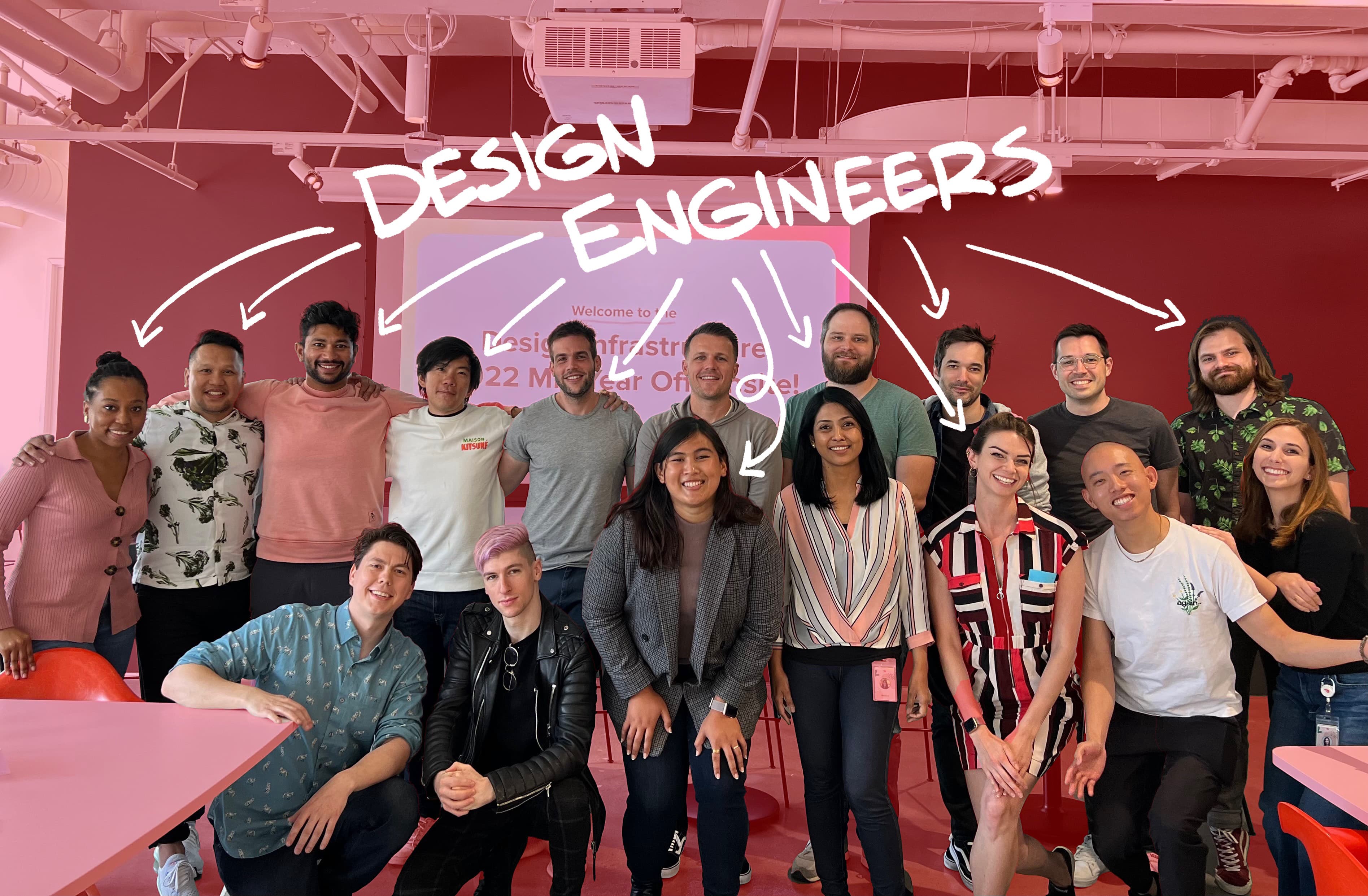

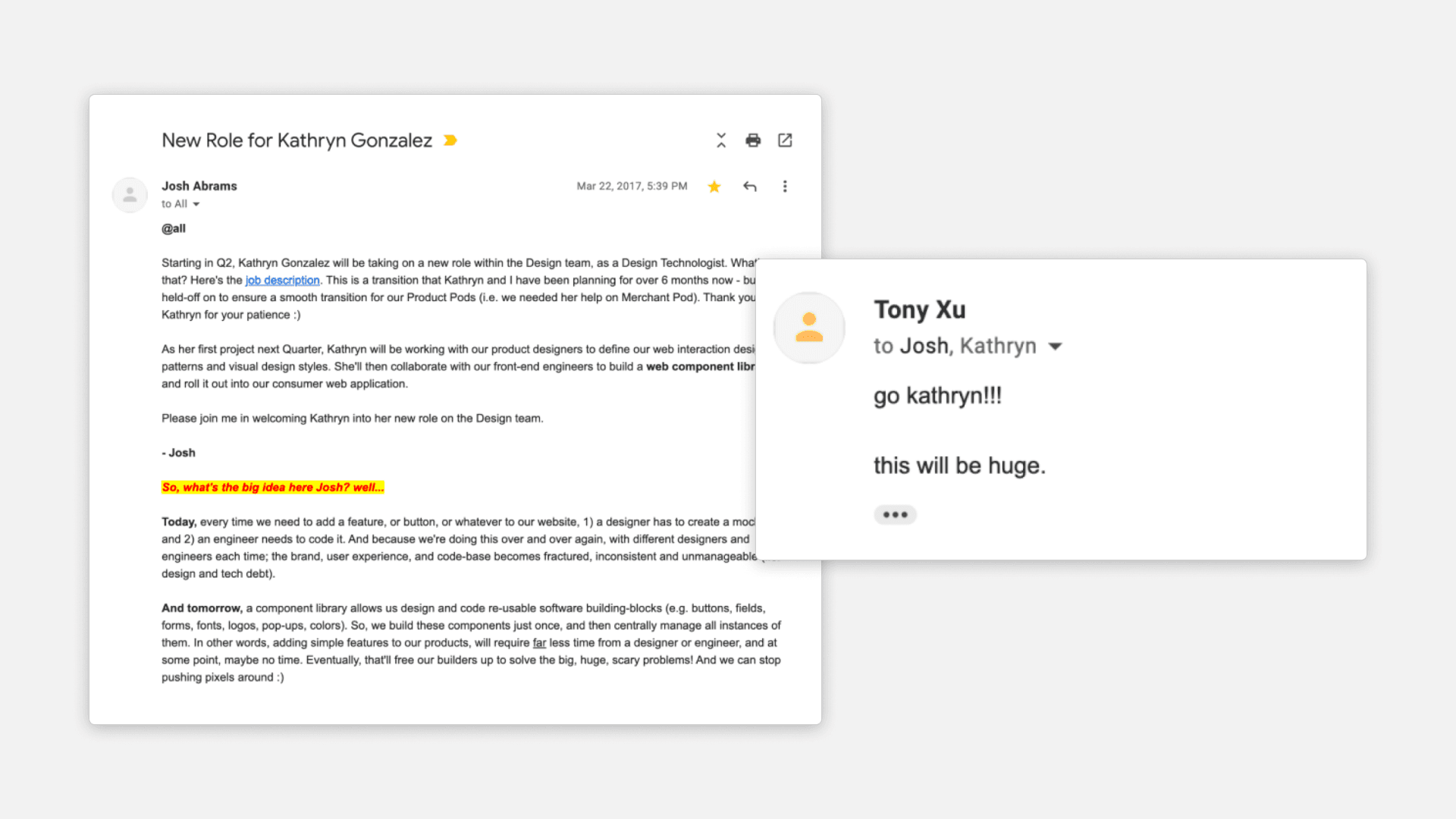

I like to say that Design Engineering at DoorDash started as a recognition that design and engineering needed to live together in one role, to be able to build exceptional products at the highest quality — that it was a very intentional, specific decision: "We're building a design engineering team!"

In truth, it started because they hired me as their first product designer, and quickly, I made it known that I didn't see the scope of my role being just a person who lived in Sketch (pre-Figma). I saw designing as just one step in making software and getting making my designs real as an integral part of that process. I'd always treated my career that way—before DoorDash I had worked as both a designer and engineer at a few different companies and agencies. I had seen the value of that work at the intersection, and I was intent on bringing that to DoorDash because of the mindset I had about building software:

In my mind, my responsibility was the full ownership of what we shipped — that the outcome, not the design deliverable, was the thing I cared about most.

When I started, DoorDash didn't have any full-time product designers and we also didn't have full-time frontend engineers. It was just a brand designer, an intern, a technical co-founder filling the gaps from the design side, and a bunch of early-stage full-stack, backend-leaning engineers building on the frontend. Because of where we were as an organization, I spent a lot of time filling that gap for both design and engineering.

I worked on both design and engineering on some projects, helping define what we wanted to do from the design and product side, and then building and launching it from end to end: things like our internal menu editor, the web version of our consumer-facing site, and even our first Merchant tools among other early projects. I shipped things that every person who used our products would see as their first impression of the product, and I made sure that impression was beautiful, designing and crafting it to my exact standards:

For both myself and the leaders who relied on me, my autonomy was a strength that we leaned on throughout my time at DoorDash — both as an IC shipping things day to day, but also as a leader who didn't have other examples of people like myself both in the company (or many outside of it) to learn from and emulate. Startups are highly motivated to hire people who can act as an owner, end to end, of the things they produce and design engineers are strong examples of how that mindset manifests in a practice.

#Practice and Teach Great Software Craft

Great design engineers are obsessed with understanding the materials of software, all the specific affordances of the medium, and the tools you use to shape them. In my experience, this obsession comes from the drive to make something that has both beauty and intentionality paired with the technical approach that design engineers develop as they strive for independence in building that software. That obsession made me the kind of person that believed this:

End-to-end craft matters — if I care about what I'm building, how it manifests in all levels of design and code, is something I should deeply understand and help others understand.

With this, you get a lot of these design engineers — aka "software makers" — that are strong at both the technical and the creative. Strong visual design and the specifics of how to render that beautiful design in both design tools and code can come easily to great design engineers.

They iterate on their skills constantly to better understand how to achieve the full breadth of their aims. They take a leading-edge approach to learning tools that others may find too intimidating technically (ex. how to apply shaders, 3D materials, physics-based animations to achieve a design) or too "wasteful" or "unnecessary" to those that were focused on getting anything that worked out the door, but not the right thing executed exceptionally well.

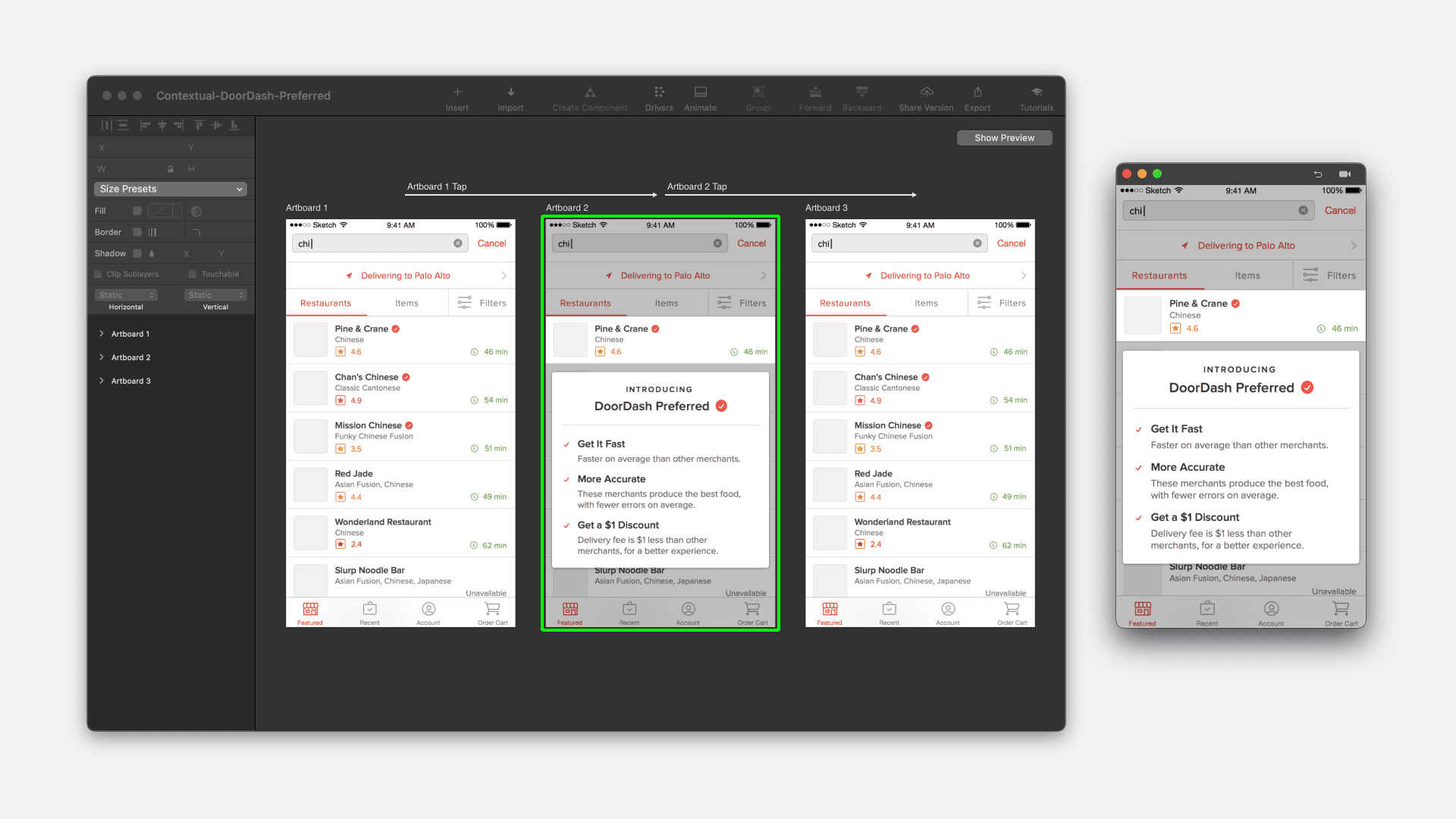

Back in the early days of DoorDash, I often took on the intersectional challenges that my focus on craft allowed me to do well. Projects that were harder to execute as a non-technical designer at the time were challenges I relished — ex. designing micro-interactions, animations, and other prototypes with tools like Principle, Framer, and straight code.

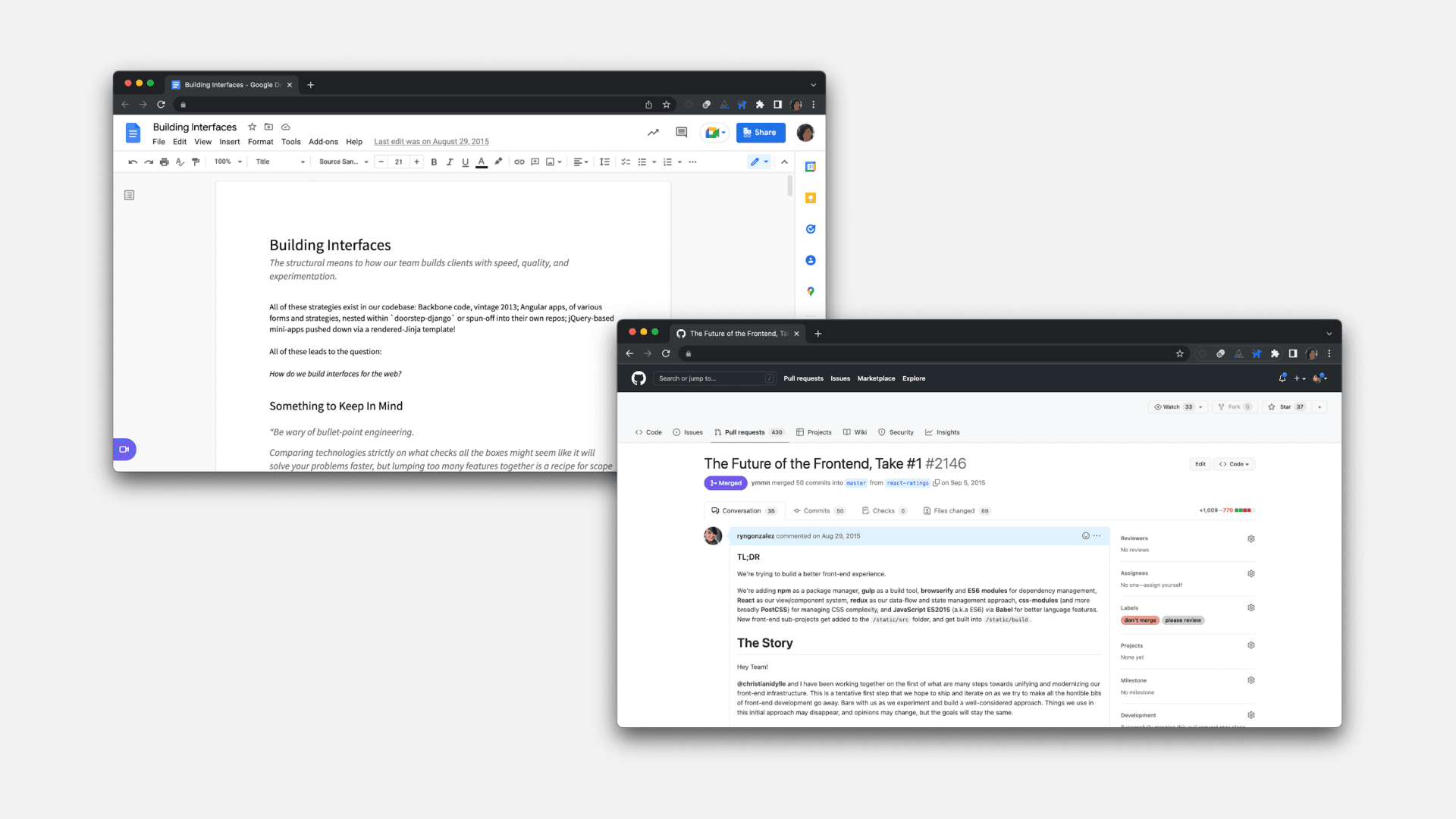

Alongside bringing craft to what I did myself, I also took on other projects that were meant to help others elevate their work and make what we shipped great. In this realm, I focused first on improving the technical infrastructure of what we were building — I migrated us to React and built the frontend infrastructure that allowed us to ship our UI code with more safety and speed, back in 2015 when React was young and our full-stack engineers had been maintaining projects in Backbone, Vanilla JS, Angular 1, of varying levels of quality and consistency.

I had some deeper experience in the past building mobile apps with a web-based stack (from my time at Fetchnotes), and from that experience had learned the intricacies of building great interfaces that felt fluid and high-craft with a medium that didn't make that easy, especially at the time. So I did a lot of sharing of that knowledge with the full-stack engineers in our organization, while also helping hire other frontend engineers with that same knowledge and attention to detail for the specifics of what it takes to build great interfaces.

#Elevate The Final Fidelity of What's Made

One of the unique aspects of design engineering is that you've got the potential to have much of the full process of building software contained in one person. That's a uniquely special place to be — you can take an idea of what you're building, and turn that into a reality at a fidelity and efficiency that's hard to achieve when you have to translate that vision between different people and roles5.

This provides some practical advantages to an individual design engineer — you can try ideas for yourself, you can build and explore ideas for others that are a more faithful rendering of the original ideas, and you can work more quickly to give what you build deeper attention to detail than if you had to work with a team of people even see it as realistically as possible.

Some of my favorite projects throughout my time at DoorDash were when we were exploring completely new product areas or difficult ideas that we couldn't express with a static set of designs, or that needed feedback that could only be gathered from a real experience. This is what I learned in my work prototyping over the years:

Selling a vision to customers, or other people in your company, sometimes requires a magic trick — something that feels like you pulled it from the future, even if under the hood it's not quite real.

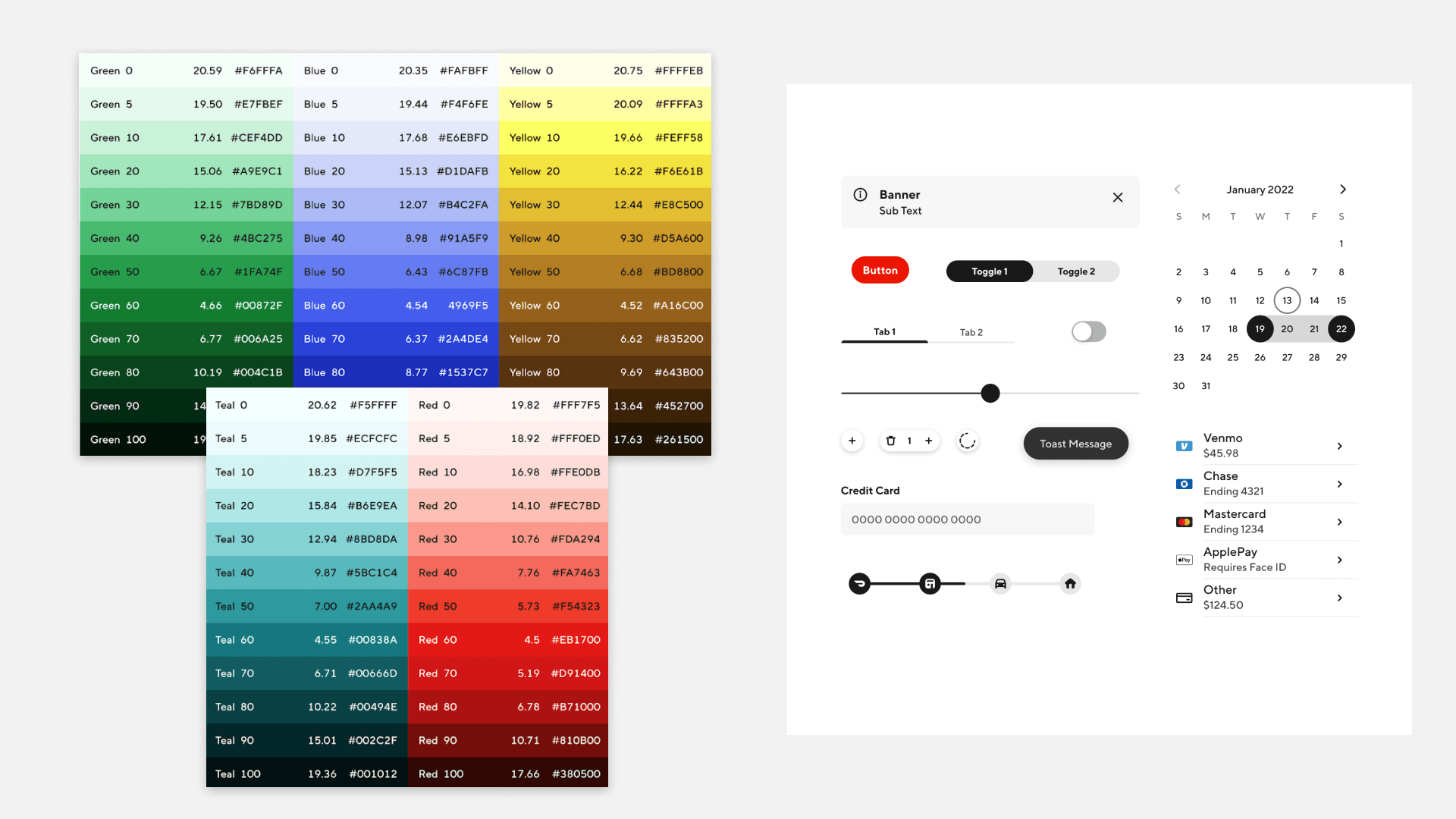

Equally useful is the fact that design engineers, in understanding how to translate between the two sides, are often great at building infrastructure that increases the fidelity and quality of the work others do. They build design systems, tools, and shared language that help bridge the gap between the other designers and engineers around them.

Ultimately, this ability is part of the reason why design engineers are most frequently found at large companies in design infrastructure and systems teams — they are great at elevating the impact of the practice of design engineering across a large scope, even if the scale of the team itself is limited.

At DoorDash, this function of infrastructure was what I found the most value in for what we needed as the company grew — we were a leading system by the time I left, and it was because of the value that we brought to the individual engineers and designers at the company in building to the quality that was needed. We were a trusted shared resource that our leadership leveraged again and again to bring the vision that we designed to fruition at a scale that was difficult to manage otherwise.

#In Summary

Design engineering is not just a designer who codes or an engineer who has an eye for design and the courage to edit a Figma file.

A design engineer is someone who sits at the intersection of both practices and who loves the craft and the materiality of building software. It's a role that requires a mindset of autonomy, and an excitement about being an end-to-end software maker. And with that expertise and mindset, what they bring to an organization is the ability to elevate what everyone builds — better software, more truthfully expressed.

Especially as our industry evolves and the ease of participating in each side of the design/engineering divide increases because of more accessible tools (hint, AI), the role of a design engineer will increasingly be a part of the organizations we build. That unique mindset, deep expertise in the breadth of software craft, and the flexibility to shift and fill needs will be more and more valued.

Still, there's so much to say about design engineering, as so much is yet to be defined in an industry-standard way. I'm looking forward to writing more posts on this topic in the coming months, covering more insights gathered from my experience, and delving into design engineering and all its facets.

P.S. If you're interested in chatting with me about design engineering, or curious about how to establish a design engineering practice at your company, reach out to me over email at kathryn@makeshiftlabs.io, always happy to chat!

#Footnotes

-

My favorite post is probably this one from @tarngerine. ↩

-

Shoutout to my friend @ohwhen who's been beating this drum for a while now. ↩

-

Looking forward to writing more about the organizational context of design engineering, how to build a design engineering team, and why being a design engineer as a career can be precarious, among other topics! ↩

-

I think the more surface-level aspects of the role have been covered well in other posts, but I expect to write about this again in a more fine-grained post soon. ↩

-

Sidenote: This is also why I believe design engineers are great candidates to be founders — their ability to bring a clarity of vision to a well-executed outcome is something that directly translates to a core ingredient of a successful startup. ↩